Several questions suggest themselves. What ideological framework is revealed by the forwarding of a contemporary story in which the white man has lost his mojo and needs to struggle to regain it? And if this is indeed the story of a white savior saving himself by saving everyone else, what is he saving himself from?

* * *

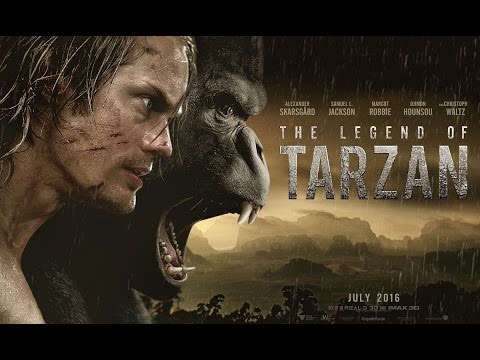

Upon its release last summer (2016), a number of reviews of David Yates’ The Legend of Tarzan rightfully focused on the movie’s troubling approach to race. In part, this trouble is inherent to the source material: it is, after all, the story of a white foreigner growing up in Africa and becoming the lord of all he surveys. It’s also a difficulty of the plot of the film’s specific version of the story. As many reviews took pains to point out, the film employs a common trope known as the “white savior” narrative, the use of which in this day and age seems rather violently ignorant, if not entirely surprising.

This is clearly played out in the main moves of the film, which are as follows. It’s 1886, and Tarzan (Alexander Skarsgård) and Jane (Margot Robbie) are fabulously wealthy and living in England. Tarzan is approached by the British government and asked to return to Africa to investigate Belgian shenanigans in the Congo. He initially refuses, only to reconsider when a black American named George Washington Williams (Samuel Jackson) explains to him that the Belgians are enslaving people. In Africa, Jane is kidnapped by an evil Belgian, Tarzan reconnects with the animals and people he knew when he was younger, and then confronts a tribal chieftain who wants to kill him. All of this is interspersed with backstory segments detailing Tarzan’s childhood in the jungle and his first encounters with Jane. At the movie’s end, he rescues Jane, frees the slaves and unites the African tribes, saves the Congo by driving away the Belgian army, and apparently decides to stay in Africa rather than return to his palace in England.

It should also be noted that throughout all of this, the film engages in a continual and remarkable series of apologetics. It opens with a short précis on the exploitation of Africa by the colonial powers. Later, George Washington Williams reminds Tarzan (and us) of the great American historical sins, including slavery and the near-extirpation of the Native Americans. This is all reinforced visually, through devices like meaning-laden shots of train cars filled with chained slaves and elephant tusks. It’s as if the filmmaker believes he understands the delicate ground on which he’s treading, and wants to be absolutely certain that we are aware of his awareness.

This, of course, makes the actual content of the film even more preposterous. But it’s also revealing. Nearly a year later, what has become evident is that this movie was not simply a white savior story. It was a prediction, a prescient embodiment of one of the hidden hearts of our cultural moment, a foreshadowing of the outcome of the election that it preceded by only a matter of months.

Begin with a question: what is it that actually encourages Tarzan to go back to Africa in the first place? In plot terms, it’s the American George Washington Williams’ invocation of slavery. In character terms, however, there is another element: Tarzan has recently suffered the loss of a child. Put differently, and more symbolically, he has been unable in the confines of civilization to give his wife a child that can survive to adulthood. This is a common trope in the action film, by which the hero is allowed to correct or overcome some personal trauma in addition to the worldly trauma addressed by the violence of the plot (think of John McLane’s sundered family at the start of Die Hard), and its construction is never incidental.

In The Legend of Tarzan, the missing son (it would be absurd, and far beyond the imagination of the filmmaker, to think of the child as a girl) is introduced at the beginning as a wellspring of tragedy for Tarzan and Jane. The film concludes, after the saving of the Congo from the rapacious Belgian army, with the triumphant birth of Tarzan’s heir. The importance of this motif is also reinforced by the flashbacks that give us Tarzan’s own history. These create a kind of parallel to our front story: Tarzan grows from infant to fully formed man, sexually and physically dominant over all he surveys, at the same time he goes from weakened, impotent man of civilization to once again dominant virile man of the wild. He is, in short, made great again.

In this way, the movie participates in a long tradition of stories about male heroes who are (sexually) born again through their engagement with the horrors/glories of the “wilderness.” In the American imagination, the locale of this adventure is usually the American West, and The Legend of Tarzan certainly makes use of certain elements of the Western movie, but its specific location is Africa. Here, the narrative of being reborn through violence is paired with another tradition, one that reduces Africa to what Chinua Achebe famously called a “metaphysical battlefield.” That language comes from Achebe’s famous critique of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, in which he pointed out that regardless of Conrad’s “great talents,” what the European writer had done was to reduce an entire continent to a radically dehumanized backdrop for an exploration of European angst about the state of its own civilization and humanity.

The racial and cultural elements in this critique resonate, of course, with white and political America’s use of the “inner city,” recently re-commemorated in Donald Trump’s vision of “American carnage.” What Achebe allows us to see is that the heart of this story is not the salvation of Africans, or African Americans, or animals, or women, all by a white dude. The heart of the story is the salvation of the white dude himself, with all the rest presented as an appreciative audience, one that is ennobled in the end not by their own transcendence, but by his.

Several questions suggest themselves. What ideological framework is revealed by the forwarding of a contemporary story in which the white man has lost his mojo and needs to struggle to regain it? And if this is indeed the story of a white savior saving himself by saving everyone else, what is he saving himself from?

There seem to be two ways to approach this issue. One would be to move back into a strict consideration of race and gender, and to say that the film should be seen as a white male empowerment film. One must say, I think, that all people deserve empowerment, and also that (as is evidenced by the opioid epidemic) everything is not necessarily peaches and cream in white America. It is also too easy, I think, to say that white people all have power and no one else does. Given those caveats, however, there is something ridiculous to the point of being actually dangerous in a film that presents a wealthy white guy in need of empowerment, particularly as that empowerment comes as a result of his (re)ascendency to what is presented as his lawful place as the “lord of the jungle.” It suggests that the issue is not one of empowerment at all, but one of rightful position.

When one becomes aware of this construction, it’s hard not to see this film as at least partly a response to any inroads that have been recently made by groups of people that are not white males, and as a salve to people who feel they’ve been (sexually or socially) emasculated by those inroads. It verges on a claim familiar to anyone who followed the wailings about the remake of Ghostbusters, or transgender issues, or Black Lives Matter, or “political correctness” or the presidency of Barack Obama: it’s really the white man who is the new victim. Here is a new (old) kind of Trumpian hero! A white man absolutely reduced by the henpecking demands of modern liberal civilization who rediscovers his power – and his ability to be magnanimous – by a return to the wilderness, to the battle, to the old sources of his dominance.

I worry, however, that the issue does not end there. The second way to answer the above questions concerns our American relationship with history. I mentioned at the beginning the feelings of contrition that emanate so strongly from the film. It attempts to focus our attention and sentiment on the tragedies of Africa, and indeed on colonial histories in general. In one of the film’s most remarkable sequences, the African American George Washington Williams explains that after fighting in the Civil War he was so full of pain and rage that he went to Mexico to fight with Maximilian’s troops against the revolutionaries, and then came back to America to fight with American troops against the Native Americans. He closes the monologue by declaring that because of these actions he’s just as guilty as the Belgians who are enslaving the Congo.

There is a breathtaking cynicism here, of course, in the vision of a black character explaining that he is as responsible for the sins of the 19th century as are the European and American colonial powers. Of perhaps more interest, though, is the film’s approach to those sins. Rather than acknowledging them as a fact of history, The Legend of Tarzan takes them as scary potentialities from which we were fortunately saved. It is an act of desperate wish-fulfillment of a magnitude that nearly defies adjectival description; it is also an act of reformatting the truth with which, I fear, we should probably continue to familiarize ourselves.

In the real world as most of us know it, Africa was not saved from colonial exploitation. There was no harmonious reconciliation of colonial masters and African subjects, no salvation of the animals and the environment, no Lion King-esque restoration of peace and tranquility. There was instead, and there continues to be, actual history. The apartheid of South Africa, the diamond lords of Namibia, the CIA’s adventures in west Africa, landmines in Mozambique, genocide in Rwanda, the recent chaos in Libya and Egypt, the near absolute oil-driven devastation of the Niger Delta, the environmental and human toll of generations of war, poverty, and usurpation, etc. etc. My point in listing only the tragedies and not the triumphs is not to suggest that the story of Africa is reducible to the story of pain; it is simply to suggest that the ending of The Legend of Tarzan can only read as something other than an absurdist joke to someone who either doesn’t know anything of history or believes that history truly can, and should, be rewritten if that rewriting is necessary in giving us a feeling of triumph. Someone, that is, exactly like Donald Trump.

It’s tempting (and not incorrect, I think) to apply that much-used phrase “white privilege” to this fiasco. Only someone who has never known the wrong end of the stick could make a film that invokes the real suffering of a continent as a backdrop for the story of their own journey from impotency to triumph, and then end the film with the insistence that not only did that journey rescue the locally involved bodies, it actually changed the course of history as a whole and eliminated that suffering. Delusions of that sort are the province of the powerful, and privilege is simply a mode of possessing power.

But it would be incorrect to say that we live in an age in which privileged white males are the only ones who want to either forget or whitewash history. There is clamoring from many sides to the effect that if the past itself starts to feel like an aggressor, then we simply wipe it away and replace it with versions of events that happened the way we would have liked them to. The Legend of Tarzan demonstrates the problem with that approach: we might like to allow ourselves to live in a fantasy world, but power, like Trump, works its awful magic in the real one.

* * *

Unless noted otherwise, all images are screenshots from the film.