When I watched Bacurau again this summer online, so much felt different: the open-air communal life of the villagers seemed even more distant and utopian; after months of Brazil’s president mocking his constituents as they died in droves, the critique of a corrupt and elitist state felt even more merited and even more on target given his callous disregard for the poor populations both rural and urban who were suffering most. But especially striking was the way the film resonated with the latest round of police violence that had filled streets around the world with protesters against systemic racism. In a few short months, history had changed the movie.

* * *

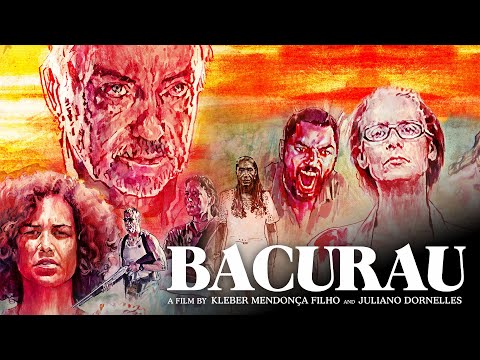

Bacurau (2019), Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles’ sci-fi-inflected contemporary Western, is full of iconic moments invoking at once the viscerally visual and aural thrills of low-budget action movies and a nuanced history of oppression and resistance. Take the moment one of the white American hunters who have paid a fortune to a corrupt regional mayor for the privilege of a human safari targeting the inhabitants of a remote village in the sertão, or backcountry of northeastern Brazil, is stalking his prey inside the deserted local-history museum. The camera scans over artifacts of rebellion and uprising, photographs and newspaper clippings documenting violent suppression of cangaceiros, or social bandits, in the first half of the 20th century. As the hunter’s eye tracks the displays, he hesitates on an empty wall marked only by the discoloration surrounding a collection of weapon-shaped negative silhouettes. The camera cuts to a series of quick close-ups featuring the explanatory label under each weapon-shaped absence: “Mauser (1908),” “Winchester 44 (1873),” “Colt 38.” After a moment’s hesitation, both the hunter and the audience realize what this means for the plot: these villagers are armed, dangerous, and ready for their attackers.

In the way of action-genre filmmaking, especially in the global South, the moment is emotionally and sensually immediate in its impact while also analytically overdetermined in its social and cultural resonances. In addition to its function as instant exposition, the visual shorthand also sets off a chain of associations: the labels work both to echo and to undercut the weapons fetishism typical of Westerns and of right-wing action fiction and websites: as one woman explains to her fellow hunters, “How did I come to love this gun. I was a babysitter in New York. And my grandfather, Mr. R., had four Thompsons and he had them in this big glass cabinet. I mean super high-tech stuff. And one day I asked him about that machine gun. And he took it out of the cabinet and placed it in my hand. [Pause] And that was that.” Typical fetishism from an atypical source. Another boasts to the two southern Brazilians who helped set up the operation, “Nobody at this table hunts with modern weapons. We only use vintage firearms.” The directors frame the wall of absent weapons against the American hunter’s sleeveless t-shirt advertising “Blackhawk! The World’s Finest Tactical Gear.”1 Terry (Jonny Mars) has previously identified himself as a clichéd epitome of toxic Trumpian white masculinity: he tells a story of stalking his estranged wife in order to kill her, being unable to find her, and twice cruising a shopping mall planning to shoot up the shoppers before something told him not to, presumably God, who, he informs his fellow hunters, has “now . . . given me the opportunity to deal with this pain here.” And the tactical gear branding associates him not only with a global imaginary of weaponized white supremacy but also with the disastrous 1993 military raid to capture a militia leader in Mogadishu memorialized by Ridley Scott in Black Hawk Down (2001).2 They may be severely overmatched by the firepower of the invading hunters, but, reassured by associations with the genre tradition of Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959) and especially John Carpenter’s urban update, Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), we now suspect they will prevail in their asymmetric battle. And the dates on the labels and museum setting remind the audience of the long history of predation and resistance of which what we are seeing is only the latest instance. It may play like fiction, but they’re also rewriting the history behind those movies.

Still, even given the prep work done by the museum’s wall, many audience members will not be prepared for what happens next: local bandit Lunga, hidden in the floor beneath a straw mat, lifts the cover just enough to shoot Terry dead with an old pistol. Following this classically guerrilla-style ambush, the film cuts to an archival still of severed heads. Lunga climbs out of his blind, grabs a machete off the museum’s wall display, and savagely hacks the body to pieces. He emerges later from the museum’s entrance, shirtless torso drenched in blood, eyes white with rage, grasping a hunter’s severed head by the hair in visual emulation of the museum’s history lesson, except that the tables have been turned: the heads in the photographs belong to executed cangaceiros; his heads, which he will eventually line up on the museum’s doorstep, belong to the contemporary avatars of the executioners. Not for nothing do Mendonça and Dornelles introduce the hunters in their base camp at an abandoned (or rented – it’s never explained) local hacienda, boasting its own archival photos of landowners and slaves, and maintained by an elderly Black serving woman. Just as the cangaceiros saw themselves as social bandits fighting the “legal” predations of the ranchers and landowners, so Lunga and the other inhabitants are fighting for their lives against violent predation enabled by corrupt authorities, or, as the hunt’s organizer Michael reminds their Brazilian enablers, “local contractors,” and not, as the latter had referred to them, “the people we’re paying to do it.”

The Brazilian operatives, who hail from São Paulo in the wealthier and more developed south, explain that they identify with the white elite descended from German and Italian immigrants, before being drily informed by the hunters that they may look white but are not. Michael complains that the Brazilians did not have permission to kill villagers (they had shot two, in a neighboring farm where two hunters had already slaughtered the entire family): first, because they took “two kills” away from the hunters, their employers; and second, because they can be placed there, thus potentially exposing the expedition. “Technically, we are not here,” he clarifies. “But you are here,” responds one of the Paulistanos. “I have documents that prove that we are not here,” returns Michael. The hunters rely on an extralegal status, as if the sertão were not Brazilian territory or the sovereign possession of legally established villagers, but a live-action version of Westworld peopled by local citizens rather than artificial humans, a human theme park analogous to the SEZs (Special Economic Zones) that form outposts of global capital operating independently of the cities or nations of the global South in which they are established to attract transnational investment drawing on local labor and infrastructure. Along with its explicit links to Brazil’s violently unequal past, Bacurau’s plot thus opens up into an allegory of corrupt multinational predation secretly abetted by illiberal state authorities. The village has been progressively cut off from the nation not so much for its remote location and arid land as for its lifeblood; before the hunters sever their lines of communication, corrupt developers had already blocked the water supply. It’s not for nothing that neoliberal development and resource mining in the global South is so often referred to by journalists, economists, and policymakers as “the Wild West.”

Bacurau in the World

Speaking with Recife-based drag artist Silvero Pereira, who plays Lunga in the movie as a gender-nonconforming outlaw, for the U.S. magazine Interview, Bessie Rubenstein asked about critics’ claims that because the film is “direct in its address of its own national politics, and unapologetically unwilling to simplify . . . that took away from the film’s enjoyment,” in particular, its genre pleasures of suspense and violent action. Pereira responded that it was not in fact an attack solely on the regressive policies and politics of current president Jair Bolsonaro, but a systemic critique, “First, this isn’t specifically about the current government. It’s about the government that we’ve always had. This film was written and produced well before the election of Bolsonaro, so it speaks about a very common type of politics, specifically about the coronéis, the landowners. They think that they own everybody.”3 What’s fascinating and compelling about Bacurau is not so much the way it mashes up politicized anger with genre tropes; rage against the system has been a staple of exploitation moviemaking since the Spaghetti Western and its rural outlaw and urban gangster descendants. It’s the ways it indigenizes and deepens Hollywood genre tropes to make transparent the inequities of the economic system underpinning those same tropes, while simultaneously turning them around, with intense satisfaction, onto the agents and beneficiaries of that system. As critic David Fear put it, they use a “termite art vocabulary to attack a bigger-picture sense of injustice.”4

For “woke” audiences coming from or identifying with an underclass or marginalized group, exploitation genres have always offered the pleasure of recognition and agency around injustices they need no reminding about; for audiences slumming from a position of privilege, those same genres certainly make available vicarious recognition of injustice and inequality. However, it’s usually pretty easy for them to adopt a viewing position that partakes of the frisson of banditry and the thrill of violent and just revenge without needing to confront the underlying causes or one’s own implication in those causes – Quentin Tarantino’s revenge dramas Kill Bill and Django Unchained are virtuosic examples of this style of filmmaking. Bacurau attempts to combine the genre thrills of Tarantino’s films with the moral clarity and gravity of the overtly politicized forms of much of global South filmmaking. One place these strategies meet is in what Brazilian Cinema Novo filmmaker Glauber Rocha termed an “aesthetics of violence . . . the initial moment when the colonizer becomes aware of the colonized. Only when confronted with violence does the colonizer understand, through horror, the strength of the culture he exploits.”5 Rocha made his own “Northeasterns,” as Brazilian Westerns have been known since the 1950s, rendering the late 19th- and early 20th-century tradition of cangaço, or social banditry, featuring “the flawed hero who has resorted to violence as the only way to respond to the consequences of a problematic government,” in the terms of a decolonizing late 1960s “third cinema,” neither mainstream Hollywood nor European avant-garde.6 Rocha’s Northeasterns such as Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (1964; Black God, White Devil) and O Dragão da Maldade Contra o Santo Guerreiro (1969; Antonio das Mortes) deployed an aesthetics of violence within a production context of indigenized experimentation. What Mendonça and Dornelles call a “political fantasy western”7 mobilizes transnational financing and grindhouse tropes – each “kill” is imaginatively staged, viscerally realistic, and unapologetically graphic – in the service of an allegory of predation and revenge that is positioned locally but aims to resonate globally in the same way as the globally popular Spaghetti Westerns of the 1960s, Bruce Lee’s righteously raging kung fu vehicles of the following decade, or gangster movies of the ’80s and ’90s.

Bacurau enacts this play between the village’s extreme isolation deep in the Brazilian sertão and its transnationally invoked audience through the myriad ways it remains linked to the urban lifeworld and to political networks both local and global. On the one hand, they carefully document the way the hunters and their local contractors systematically cut the village off from the outside world. First, Tony Junior, the corrupt municipal mayor, cut off their water by blocking the source upstream of them. Next, the hunters’ contractors block the road, including the water truck that has kept the villagers supplied since that time. As the hunters tighten the noose, they digitally erase Bacurau from Google Maps, block cellphone service, and, finally, cut the electricity. On the other hand, despite its physical isolation, Bacurau had in fact until this point been fully networked with infrastructure and supply networks – not, perhaps, reliably or to elite standards, but to the degree that every inhabitant appears to have a cellphone and the schoolmaster teaches with a networked tablet, a desktop computer, and a smart classroom. Even the school’s name, Escola Municipal Prof. João Carpinteiro, the co-directors’ tongue-in-cheek homage to the B-movie maestro, whose synthesizer composition Night also graces a capoeira scene, signals the villagers’ worldliness.

The film’s opening stresses both the village’s connectedness and its isolation in a number of ways. Mendonça and Dornelles begin in outer space, as a sequence of shots slowly zooms in to show us the South American continent, recalling satellite photos of the world at night deployed as evidence of the unequal distribution of the electric grid and other modern infrastructure. The sequence eventually dissolves to a water truck on a one-lane blacktop, identified by a title as “Western Pernambuco,” the northeastern state that sprawls westward from the directors’ coastal home base of Recife to the inland plateau of the sertão. A second title cheekily informs us that we are “A few years from now,” establishing a temporal continuity and causal line between the mythic past of the conventional Western iconography and the imagined future of science fiction. Within that space, Mendonça and Dornelles will painstakingly develop a materially grounded ethnography of a present peopled by nonprofessional actors in both speaking and nonspeaking roles, before exploding that ethnography with violence both mythic and historicized. “If You Go, Go in Peace” reads a directional sign 17 km (presumably) outside of the village. By the end of the film, Hope for the best, plan for the worst, suggests itself as better advice.

The driver is carrying a passenger, Teresa (Bárbara Colen), who is clearly marked by her fashionable jeans, hairstyle, boots, and bright-red roller bag as a wealthy city woman, stand-in not only for the audience but also for the filmmakers. While self-identifying as outsiders from the poorer north of the country, Mendonça and Dornelles are equally aware of their status themselves as privileged outsiders in relation to the remote location to which they traveled to film Bacurau, a radical turn from their resolutely urban, Recife-based, and upper-middle-class-oriented pair of earlier features, O Som Ao Redor (2012; Neighboring Sounds) and Aquarius (2016).8 Of Bacurau’s characters, only Teresa could fit easily in the world of those films, and the audience can readily identify with Teresa as the conventional vehicle for an ethnographic journey into a remote and exotic land. The directors heighten the effect of Latin-American exoticism with an eerily magical realist touch: the isolated highway is suddenly strewn with coffins. That this surreal imagery resolves into a fatal highway accident and pairs magical realism with cynical Leonean fatalism suggests the fluent playfulness of the film’s deadly serious intertextuality. “We’ll take two,” the subtitle reads as the truck approaches the accident, presumably referring to the wife’s need to bury the husband lying dead in the road beside her.

The World in Bacurau

The hinted genre payoffs are slow to emerge, however; instead, the filmmakers painstakingly detail the everyday life of the village, its tight community, and the ways it has survived and resisted the corrupt systems around it through a loose assemblage of informal means and a frontier sense of ethics and legality. The driver quickly fills in Teresa on the current crisis: four months back, the town’s water access was blocked upstream by the municipality’s mayor; Lunga tried to open it up; she killed three men and is now in hiding.9 Not the typical urban observer, it turns out, Teresa quickly responds, “Don’t expect me to turn Lunga in.” Although Teresa does not present as the mysterious stranger riding into a Western town, her response certainly establishes her as a local and places her firmly in the Western context of self-sufficient isolated townspeople and the good/bad gunslingers they turn to for help. It turns out that her roller bag is packed neither with urban fashion nor with a cache of firearms; instead, she brings precious drugs for the village clinic, carefully packed against the heat. She brings assistance against the local strongman, just not in the conventional form. The strongman, Tony Junior, rolls into town the next day, clad in the cowboy boots, jeans, and Lacoste shirt of a rancher elite, come to buy their votes with food, drugs, and books.

Alerted to Tony’s arrival, the villagers shelter in their homes, refusing even to acknowledge his presence, much less promise their vote; afterwards, they assemble in the plaza to process what he has left behind. They warn each other about the expired dates on the food and the side effects of the drugs and sift through the books (dumped from the back of a truck) to separate the junk from what their library can use.

In its deliberate pacing, loose plotting, and sparing exposition, the film’s first half participates knowingly in what we might call the global South movie genre of ethnographic realism. Typically shot like Bacurau on location using nonprofessionals as extras, also in speaking roles, and sometimes in feature roles, but more often supporting a few professional actors, such films document indigenous beliefs or local cultures, often focus on children, usually start badly, depict a lot of suffering with a few fleeting moments of respite, and often end as hopelessly as they began. Some especially effective and broadly distributed examples, to keep within the Brazilian context, would include Vidas Secas (1963; Barren Lives, dir. Nelson Pereira dos Santos), Erendira (1983, dir. Ruy Guerra), Central do Brazil (1998; Central Station, dir. Walter Salles), and Cidade de Deus (2002; City of God, dir. Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund). Indeed, the long early sequence that documents the funeral of Teresa’s grandmother Carmelita, the 94-year-old village matriarch, raises audience expectations for precisely this kind of film. Domingas (played by Brazilian movie legend Sônia Braga) greets Teresa and the grieving family with an obscene tirade attacking the legacy of the matriarch. The next day, led by the village troubadour, the entire village sings their signature song as they accompany Carmelita to her final resting place: “Now is the time for the bacurau / The jaguar dances forward / The capora and babau dance / A feast of fear and terror / Phantoms haunt the wake / . . . / Spells are floating in the air / The work of an evil sorcerer.” The sequence ends on a hallucinatory image of water pouring out of Carmelita’s coffin. But even as they stage the scene with unironic pathos, the co-directors work to historicize and contextualize their magical realism. Carmelita is played (in a nonspeaking role) by Lia de Itamaracá, legendary Pernambucan dancer, composer, and singer; conversely, the song about the bacurau, a species of nightjar (later described by one villager as a nocturnal “hunter”), is not the folklore it pretends to be, but was composed for the film by Mateus Alves and Tomaz Alves Souza. The procession is led by town crier and local DJ Urso (Junior Black), with Carmelita’s memorial image projected on the giant TV screen mounted on the back of his pickup truck. And Domingas, who turns out also to be the village doctor, apologizes to the community for her behavior of the previous night.

Ethnographic realism can be extremely effective in calling attention to and eliciting sympathy for the difficult lives and extreme conditions that frequently characterize the lives of the dispossessed in the global South. But it affords little space for complexity and complicity on the part of the viewer, instead sparking distanced sympathy and emotional catharsis, as if merely the act of watching constitutes ethical action and will lead to change. Mendonça and Dornelles have explicitly described their recourse to popular genre tropes as a response to what they perceive as the limitations of this kind of ethnographic filmmaking:

Our desire to work with genre actually came from a profound discomfort that we felt when we first began thinking of our film – which then took us some 10 years to complete – with certain representations in cinema, particularly in Brazilian cinema. I have in mind the ethnographic representations that frame persons living in far-away places as somehow “exotic” or “simple.” At that time, we would see this particular phrase, “a simple person,” appear in some festival catalogues, directly in the synopsis. We saw how this led to equivocal representations, despite directors’ best intentions. Which is why we wanted to show a community that completely breaks with the idea of what is “simple.”10

The directors have equally described their use of transnational genre tropes to destabilize the binary equation between developed “sophisticated” global North and “simple” global South which they regard filmmakers too often to be echoing. And their strategy of inclusivity – lesbian couples, Lunga’s gender nonconforming identity, a trans couple with a child who keep the village watch, in addition to the wide range of skin color – participates in a similar worlding of an ostensibly “backwards” and isolated community.

Because it has been used – from Seven Samurai or Rio Bravo to Precinct 13 – primarily to dramatize internal rather than colonial or other external power dynamics, the village-under-siege scenario works to draw the viewer into identification with the inhabitants rather than observing them from a distance. In the battle for Bacurau, every combatant originally hails from the village itself – there are in fact no outsiders, not even Teresa. And the villagers themselves are nothing if not worldly. Teresa’s occasional lover, a former hitman and member of Lunga’s gang who has now changed his name, returned to the village, and gone straight, is a YouTube celebrity because of “Trigger King Pacote”; the villagers gather at night around the big-screen TV mounted on the back of DJ Urso’s pickup to watch a compilation of surveillance videos of his execution-style murders in cities across the northeast. Some additional examples: When a village elder sees a flying-saucer-shaped drone appear in the sky, rather than being frightened or nonplussed, he knows exactly what he has seen, down to the pop-cultural reference: “I saw a drone. Like a flying saucer from some old movie. But it was a drone.” The villagers discover, ominously, that they have been digitally wiped from the map when their schoolteacher wants to show his pupils the village on satellite imagery on his tablet. And a beautiful nocturnal sequence that begins with a dreamlike premonition of the violence to come and an iconic Westerner shot of a stray mongrel on the deserted street, leads to a stampede of riderless horses, and concludes the next morning with two modern cowboys mounted on horses, talking on their cellphones as they prepare to return the horses to the local ranch. The villagers are as fluent in social media and digital technology as they are in the ways of the sertão, and they seamlessly navigate between them in order to survive.

Nor do the inhabitants of Bacurau have any illusions about the benevolence or reliability of the outside world, its systems, or its figures of authority. Unlike the Black police lieutenant in Precinct 13 equally cut off from the outside world by a murderous LA gang bent on revenge, the villagers of Bacurau voice no empty nostrums that they’re in the middle of a city and someone has to hear the gunshots; or that they’re in the middle of the city and someone will have to notice that the phone lines have been cut. They do not respond to the attack on Bacurau as an unforeseen interruption of their regular lives; rather, their behavior makes clear that this is simply an extreme instantiation of the kind of harassment and violence they are well accustomed to dealing with. The details of that harassment and violence are there to be gleaned among the ethnographic observations. There’s the family on the edge of town who phone in whenever someone approaches on the one road. There is the hidey-hole beneath the village plaza. There’s the aforementioned munitions supply on the museum wall. And there appears to be a well-established emergency plan as well. When the attack finally comes, the villagers shelter in place: some in points of ambush around the village, some in the hidey-hole, and some in the schoolhouse, whence they emerge at one point to shoot back.

The World Opened Up in Space and Time

As the filmmakers diverge from the genre conventions of ethnographic realism and lean into the sci-fi and action tropes they had judiciously scattered through the first half of the narrative, they extend the film’s reach in both space and time. Even as Bacurau has been intentionally cut off from the outside world, the audience comes to understand how present that world nevertheless remains; many of them may also come to understand that world differently. Mendonça and Dornelles filmed Bacurau in a quilombo, a village founded by escaped slaves.11 Like the museum, close-up inserts remind us of the way the past remains present: as Michael (played with gusto by Eurotrash icon Udo Kier) stalks through the ruined hacienda, he passes the remains of a Massachusetts-produced cotton gin, material trace of the slave labor that drove the economies of both nations and seeded the systemic racism that continues to plague both nations despite the protestations of their respective leaders.12 The hidey-hole, with its iron-grated entrance, is powerfully ambivalent as a space: it may have been built to imprison slaves in solitary confinement or it may have been constructed to hide from the authorities. What’s beyond question is its current purpose: to bury Michael alive in the final act of the villager’s revenge upon its attackers. The quilombo’s radicalism is updated in response to the 21st-century context of President Jair Bolsonaro’s reactionary policies: the populace is racially mixed and highly tolerant of the LGBTQ members of its community, including Lunga, whose ferociously violent revenge drives the bloodbath at the film’s end.

In the memorial service for the victims of the hunters’ violence, the villagers recite the names of their dead while snapping photos with their phones of the trophy heads lining the museum’s stoop. As if calling our attention to the utterly ordinary appearance of this bloodthirsty mob, Pacote asks Teresa if she thinks Lunga went too far. “No,” she flatly responds. Domingas’ partner directs the cleansing of the blood-spattered museum. “We’ll clean it all up good and scrub the floor” she begins. “But leave the walls as they are,” she continues, pointing to a bloody handprint. “I want it to stay like that. Exactly as it is. Unfortunately.” Their lives continue and they continue to be informed by the history that has gone before and still includes them. Tony Junior pulls up in a shiny minivan. As he walks toward the villagers, a bucket of bloody water sprays at his feet, thrown from the museum’s entrance. The minivan driver opens the sliding door to show an array of empty bucket seats, a bottle of water in each one, ready for the “tourists” he has come to pick up. “What happened?” he asks. “Where are the gringo tourists?” As his gaze rests upon the row of severed heads and the villagers’ stone-faced expressions of fury, he offers to resolve “the water issue.”

Rather than resting on this local conflict, the denouement pairs Tony Junior’s fate with German-born American Michael’s. As the mayor attempts to bargain, an old man in a cowboy hat walks Michael into the plaza at gunpoint. “Tony,” Michael shouts, in desperation. “Amigo. What happened? You promised. Dinero.” Tony’s fate is an indigenous exorcism of a contemporary scourge: in a long tracking shot a wizened little woman strides up past the long row of coffins and the watching villagers, holding up a homemade mask. Domingas, her white medical coat stained with blood, puts it over Tony’s head as he sits, stripped to his briefs, backwards on a donkey, to be sent on his way into “the Bacurau caatinga,” or desert. “May he find there the inner peace he so sorely needs,” continues DJ Urso on his loudspeaker. “He brought pain and suffering to this community. Today, we in Bacurau say goodbye to this demon. Hopefully, it’s the last we’ll see of him.” Michael’s fate is less open-ended and echoes the other side of their history: he is sealed in the hidey-hole to die. The masked exorcism either copies or emulates a local custom or deity; imprisonment to the death in a sun-backed prison cell, on the other hand, reflects the treatment of slaves the world over. Rather than correcting or replacing ethnic or magical realism with the transnational post-Western, Mendonça and Dornelles have crafted a novel hybrid in which each form nourishes and corrects the other.

Bacurau was the last movie I saw in the cinema before New York City instituted a shelter-in-place lockdown back in March as a measure against the spread of COVID-19. My timing could have been better: I discovered when I got to the IFC cinema in the West Village for the last show of the night that the screening would start late because the filmmakers were still in the theater taking questions from the audience following the prime-time screening. The lobby was full of members of the local Brazilian arts community milling around visiting. Once inside the cinema there was a sparse scattering of spectators, well separated around the theater; everyone in the know had been to the main event. When I watched Bacurau again this summer online, so much felt different: the open-air communal life of the villagers seemed even more distant and utopian; after months of Brazil’s president mocking his constituents as they died in droves, the critique of a corrupt and elitist state felt even more merited and even more on target given his callous disregard for the poor populations both rural and urban who were suffering most. But especially striking was the way the film resonated with the latest round of police violence that had filled streets around the world with protesters against systemic racism. In a few short months, history had changed the movie.

Reviews of the film when it first played at Cannes in 2019 had lauded it despite what a number of critics saw as its heavy-handed and flat-footed allegory of predatory Anglophone white elites murdering Black Brazilians with impunity.13 In the light of the protests and the discourse around them, that “obviousness” now felt like a valid rhetorical strategy for addressing white audiences that otherwise could simply continue choosing not to register what they were seeing, as it was clear we had been doing, over and over. The limitations of ethnographic realism seemed a similar strategy: like similarly ethnographically oriented Black filmmaking, such films could readily be consumed by white audiences at a distance, affective but not activist, as for years many of us accepted the opposition of Radio Raheem’s lynching and the destruction of Sal’s pizzeria in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) as a balancing equation rather than a demonstration of false equivalency. The factitious argument between Bacurau’s hunters over whether or not their rules allow them to kill children or only adults; the point-blank shooting of a child innocently playing with a flashlight; the unprovoked attack on a villager as he waters the plants in his greenhouse; the emptying of round after round from that vintage Tommy gun into the schoolhouse; the vacuous denials of Tony Junior and the facile rationalization of the two Paulistanos about the violence they had aided and abetted; the dignity and ferocity of the villagers opposed to the casual entitlement of the hunters; Michael’s appeal to the immunity-granting power of his whiteness and his money until the moment he is sealed underground; the inclusive humanity of the Bacurau community in the face of lawless force enabled by legal authority – if any moment called for the stark moral clarity of both revenge actioners and what Bertolt Brecht called Lehrstücke (pieces for learning), Bacurau had found that moment.

It is hard to know what the “real world” effect will be of the brilliant cultural work of Mendonça, Dornelles, their actors, their crew, and the broad community employed in the “800 direct and indirect jobs this filmmaking generated,” as a sentence in the credits flirts with virtue-signaling to inform us. The very circumstances that made it, for me, especially relevant, will certainly not help it to reach the wide audience it deserves. But there’s no denying how exhilarating it is to watch this imaginative, sly, passionate, and fiercely intelligent remix of the myriad formal resources of so many decades of moviemaking and the turbulent local history at the disposal of an open-minded and talented team with a clear moral vision and a political axe to grind. And if part of change is telling familiar stories differently, there feels like a lot of potential change wrought up in this message from the remote backcountry of Western Pernambuco. It strikes close to home.

* * *

All images are screenshots from the film.

- According to the company Webpage, Blackhawk was founded in 1990 by a former Navy SEAL as a “leading provider of innovative outdoor products that enable our customers to achieve rugged independence in the activity of their choice.” Prominent among their product lines is “Shooting Sports.” [↩]

- The immediate reference in the film’s title is to a type of military helicopter; Black Hawk was a celebrated Native American war chief who led Sauk warriors in the 1832 Black Hawk War. [↩]

- Bessie Rubenstein, “Drag Artist Silvero Pereira on Getting Blood-Soaked in Bacurau,” Interview 6 March 2020: https://www.interviewmagazine.com/film/silvero-pereira-bacurau. [↩]

- David Fear, “‘Bacurau’ Review: An Exploitation-Movie Gem, Made for the Politically Exploited,” Rolling Stone 7 March 2020: https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-reviews/bacurau-movie-review-958199/. [↩]

- Glauber Rocha, “An Esthetic of Hunger,” New Latin American Cinema, Volume One: Theories, Practices, and Transcontinental Articulations, ed. Michael T. Martin (Detroit: Wayne State University Press), 59–61; qtd. in Chelsea Wessels, “An Imperfect Genre: Rethinking Politics in Latin American Westerns,” in MaryEllen Higgins, Rita Keresztesi, and Dayna Oscherwitz, ed. The Western in the Global South (New York: Routledge, 2015), 183-97, at 189-90. [↩]

- Wessels, “Rethinking Politics in Latin American Westerns,” 192. See also W. D. Phillips, “O Cangaceiro (1953) and the Brazilian Northeastern: The Western ‘in the Land of the Sun,’” International Westerns: Re-Locating the Frontier, ed. Cynthia J. Miller and Riper, A. Bowdoin Van (New York: Scarecrow Press, 2013). [↩]

- Helen Barlow, “‘Bacurau’ Filmmakers on Pulling Inspiration from Brazil’s Broken System,” Collider 6 June 2019: https://collider.com/bacurau-interview-kleber-mendonca-filho-juliano-dornelles/. [↩]

- On the earlier films, Dornelles was credited as production designer and Mendonça as director; they share directing credit on Bacurau. [↩]

- According to the English subtitles, the driver uses “she”; Lunga’s gender identity is never specified, so I have referred to Lunga as gender nonconforming and followed the actor Pereira’s usage of “he.” (Rubenstein, “Drag Artist Silvero Pereira“). [↩]

- Ella Bittencourt, “Interview: Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles,” Film Comment 21 May 2019: https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/cannes-interview-kleber-mendonca-filho-and-juliano-dornelles/. [↩]

- Bittencourt, “Interview”; Manohla Dargis, “‘Bacurau’ Review: Life and Death in a Small Brazilian Town,” New York Times 5 March 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/05/movies/bacurau-review.html. [↩]

- There should be no need at the current historical moment to document this fact in the U.S. context; for a recent account of analogous circumstances in Brazil, see Anakwa Dwamena, “How Jair Bolsonaro and the Coronavirus Put Brazil’s Systemic Racism on Display,” New Yorker 8 July 2020. [↩]

- See, for instance, John Powers’ remark that, “As a political fable, Bacurau isn’t what you’d call subtle, though” (“Mysterious Events Disturb a Small Brazilian Town in Genre-Busting ‘Bacurau’,” NPR.org 4 March 2020); Jonathan Romney’s note of “a certain amount of overstatement and indeed stereotyping” around the villains (“Film of the Week: Bacurau,” Film Comment 17 May 2019); or Peter Debruge’s unfavorable comparison of the “uneven” performances and “amateurish” dialogue of the English-speaking villains to Quentin Tarantino’s “naturally . . . hair-bristling anticipation of imminent violence” (“Film Review: Bacurau,” Variety 15 May 2019). [↩]