Here in America we have something that, with the straightest of faces, we call our Film Heritage.

What people usually mean when they invoke this solemn, unconscionably sentimental honorific is not just any movie made here in these United States, but a specific kind of movie: Something more or less old, and at one time accorded a form of honor (industry awards and acceptance, vast commercial success, etc) deemed permissible by the caretakers of our culture. That these keepers of the cultural flame generally know and understand nothing about motion pictures is something little remarked upon in public. It certainly doesn’t seem to bother anyone . . . anyone other than those who actually care about the medium, that is . . . that the movies, as well as the moviegoers, said to represent our so-called ‘Heritage’ entail but a small fraction of the cinematic experience in this country.

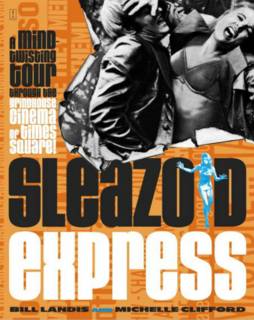

In Sleazoid Express (2002), two tireless cinephiles, Bill Landis and Michelle Clifford, expose and explore something closer to our actual film heritage. What falls under the microscope in this volume is a specific time and place in the annals of American moviegoing: the halcyon days of Grindhouse Cinema on The Deuce, Manhattan’s Times Square, where a series of crumbling, rat-infested movie dumps . . . originally designed in their day to recreate the scale and opulence of such venues as the Opéra-Comique . . . offered diversion night after night, day after day to an audience consisting mainly of wineheads, junkies, madmen, TV hookers, johns, hustlers, pickpockets, derelicts and a few unsuspecting tourists every now and again.

Strung like Arapaho beads among the Playland Arcade, the Live Nude shows, the Adult Bookstores, Peep-Shows and Triple-X houses of 42nd st., a group of once-‘legitimate’ cinemas such as the Lyric, the Harris, the Avon and the New Amsterdam (where no less than Florenz Ziegfeld staged his “Follies” so many lifetimes ago), played host to an amalgam of New York City low life who gathered therein to behold . . . basically, anything you could run through a projector. They didn’t care. These were not studious, discerning cinephiles who marched into repertory and revival houses like the British forces at Balaclava to exult in the splendor of the Moving Image. The people who went to Grindhouses had come in out of the endless twilight that was their lives usually for more prosaic reasons: To sleep, perhaps; to give a quick $10 blowjob; to get a quick $10 blowjob; to lift a few wallets, maybe; to escape the voices inside their heads. Any reason at all. And if you caught a movie while doing it, then that was just fine. In fact, anything to divert their attention was fine. If only for just a moment . . . or for a night.

So that’s what proprietors of Grindhouses gave them: Refuge from their daily nightmare in the form of Splatter films, Blaxploitation, Spaghetti Westerns, Kung Fu melodramas, Italian Zombie pictures, Old School Nudies, Soft-core Porn, Hard-core Porn; anything cheap and fast, preferably with vast quantities of blood or tits or both. For anyone from another time . . . which might as well be another planet . . . who walked into one of these joints harboring any delusions about moviegoing, it represented a quick, razor-sharp schooling in the way many Americans consume the art of Cinema.

Longtime Times Square habitué (and unrepentant biographer of Kenneth Anger) Bill Landis writes about the time and the places and the movies therein with just the proper degree of affection and respect. This book may be a remembrance of things past, but it’s not a treacly one; nor is it sanitized. He and his co-author Michelle Clifford hold back nothing. You get it all in Sleazoid Express; in vivid, almost Technicolor detail. Theirs is an effort to set down some sense of what 42nd st. Grindhouses were like in the days of their immense, gaudy decay; what it entailed to actually sit inside one of them and see a movie you would very likely never be able to see anywhere else. Now that the era has long since passed, and Times Square in its present incarnation seeks to offer up a family-friendly (read: tourist-friendly) environment while visually approximating the neon sensory-overload of downtown Tokyo, this book could not be a more crucial document in the canon of film writing.

I mean, perhaps it’s only me, but there’s just something fundamentally American about troubled individuals in a vast urban setting gathering together in a falling-apart movie theatre originally designed to look like La Scala and watching Cannibal Holocaust on a screen the size of a midwestern liquor store.