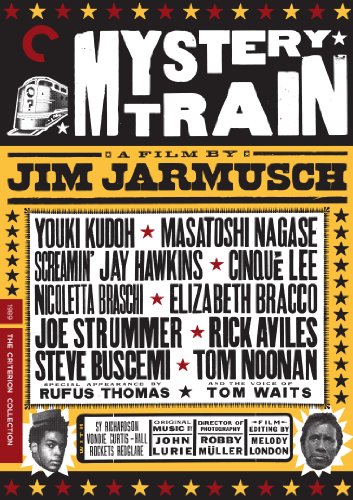

The wandering motif might as well be called Mystery Train – officially the title of Jim Jarmusch’s 1989 film now released on DVD by Criterion – which could also describe the filmmakers’ aesthetic. Jarmusch loves these wanderers so much that he finds three narratives for his film. In each, a character finds him/herself in new place and situation (or just the latter, in one case), then attempts to rationalize the ordeal before departing. The plot shape reflects Jarmusch’s style, which implores us to find our own mysteries. He has refreshed it in other films: the excavated western Dead Man, Broken Flowers, Night on Earth (the title just trailing Mystery Train as most reflective of its filmmaker).

In Train, Jarmusch brings the motif to different perspectives of Memphis, Tenn., which in this film is a town stranger and more wonderful than any place on earth. The first narrative, called “Far from Yokohama,” concerns a pair of Japanese tourists who deflate any stereotype America has attached to such. They search for the place that birthed American 1950s rock, until the film reveals that such is beyond place. The terrain has its own mysteries and, like the characters in the other tales, the couple ends up at a run-down hotel on the edge of nowhere. Earlier that day their tour of Sun Studios, the place that captured many a great tune, reveals that the music shot far from its birthplace. The characters hardly realize this, and continue their journey the next morning.

Centering the second narrative, titled “A Ghost,” is an Italian woman, Luisa (Nicoletta Braschi), who’s laid over in town. Just trying to move on, she gets caught up by urban legends about Elvis. When in a diner, she hears the story from a character played by Tom Noonan – remembering that he played the serial killer in Manhunter adds a current of menace, especially when his character bothers her on the street afterward. She asks a broke, logorrheic American woman to share a hotel room with her. When the latter falls asleep, Luisa sees the cultural icon come to her, as Memphis comes to life in the spirit of legend.

The final narrative, called “Lost in Space,” is a tongue-in-cheek reference to the title, while it nicely reflects its characters. They are dive-bargoers (including Steve Buscemi and Joe Strummer) with lives as boring as you’d imagine. With some deceit and an impulsive action, they end up embarking on a unlikely robbery. Even if the two other narratives feature actual strangers to Memphis, these locals are the true aliens. Their hideout is the hotel, staffed by what could be two gatekeepers before a spaceship (Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Cinque Lee, Spike’s brother).

The sinews running throughout are reflections on pop culture – how it’s part of time and place, though still universal. Along with the continual spirit of Elvis, the film comes across the last narrative’s eponymous 60s sci fi show, a call for Mickey Mantle and Tim McCarver (!) to become president and VP, and the late Screamin’ Jay in the flesh, who acts like a philosopher about to leave his dormancy. Jarmusch, as an interview subject, celebrates the latter in an excerpt from the 2001 doc, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins: I Put a Spell on Me (among the extras that also include an original doc on Train and Q and A session with Jarmusch). The filmmaker would dismiss much of the pop references as weak life forms swimming around us. By releasing Mystery Train, Criterion brings back a fine document: once it plants itself within, it remains a vivid cultural memory.